This blog brought to you by Funhog Press

There was hardly a wisp of wind as we stroked through a small glassy swell. The channel, that huge intimidating monster, was now a pretty stretch of open water beneath sun dappled mountains. In two hours, we were on the far side enjoying a bag of highly-anticipated cookies that had been carefully held under Diana’s ration key for days. Once the cookies were gone, we turned over rocks looking for worms that Roberto could use as bait.

Granite cliffs held powerful waterfalls crashing directly into the sea. An old wooden rowboat appeared on shore. We shouted as we passed, but raised nobody. Around the next point, the mystery was solved with a small wood-shake hut at the back of a small bay. Mate’ rounds circulated as a woman with chiseled features and striking black hair slowly spoke, her toothy smile lighting up at our curious comments. She knew the beach where we’d been stranded. She was once there for seven days, she said, waiting on the wind.

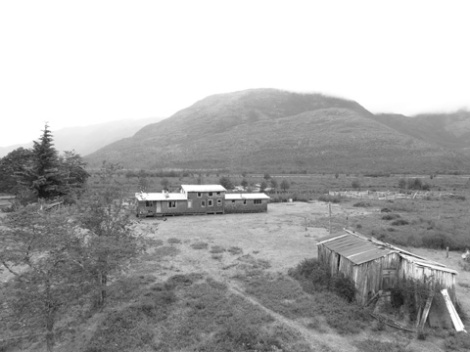

After getting a radio message out, which slowly spread uncertain news of our well-being to the world, we took turns warming ourselves by the corner stove. The hut walls were papered with dog food bags, tacked up to shield Patagonian winds that would otherwise whistle through the cracks. Sunlight pierced through tiny windows of plastic and glass. The nearest town, Tortel, required a seven-hour rowboat ride for the woman and her husband. Still, they offered us hot plates of fish and rice. We gratefully gobbled down our first full-size meal in days, and hit the water recharged for the end of our journey.

A police boat motored up the channel. One or two days earlier, I would have welcomed the sight, but now we were so close to finishing I wanted to complete the journey under my own power. But that option had passed. The rescue effort was launched sooner, but the seas and skies were too much for them just as they were for us. We motored into Tortel while chatting with our rescue commitee, imbued with a new appreciation for Patagonian weather, and satellite phones.